Netting Construction: Knotless, Twisted, Braided & Woven Explained

Table of Contents

I’ve watched nets “mysteriously” fail in the same places again and again: the two anchor corners, the bottom edge that scrapes a frame every setup, the strike zone where impacts cluster like a heat map nobody wants to admit exists. And buyers keep getting sold yarn thickness as the answer, when the real answer is structure—how the strands are built, joined, tensioned, and forced to absorb shock. Want a net that survives thousands of hits instead of hundreds?

Then you spec netting construction, not vibes.

So here’s my blunt breakdown of knotless netting, twisted netting, braided netting, and woven—what they’re good at, what they hide, and which one to pick when the application is real, not hypothetical.

Knotless netting

Knotless is my default for repeated impacts. Why? Knots are stress risers. Hard points. Tiny abrasion factories. Remove them and you usually get cleaner load distribution and more consistent rebound. You also reduce the “ball kicks weird off the knot bulge” problem that anyone who trains seriously notices within five minutes.

But. Knotless can lie to you.

If the joining method is sloppy, you get mesh deformation—bagging, sagging, opening—especially in high-impact strike zones. You’ll feel it when the net starts behaving like a hammock. This is why “knotless” only matters when the whole system is engineered for impact and retention, like a true cage setup built for repeated golf contact rather than decorative containment. If you want a reference point for what that category looks like, start here: professional golf hitting cage net for indoor/outdoor use

Twisted netting

Twisted is the budget workhorse. It’s familiar. It’s everywhere. It often looks “strong enough” out of the box. And that’s exactly the trap: twisted strands can relax under cyclic load. Repeated impacts can nudge twist into creep. Geometry shifts. Rebound shifts. Mesh openings change.

Short sentence: It drifts.

The other twist problem is abrasion—especially at attachments. Hooks, bungees, edge lines, tie points. The net doesn’t fail randomly; it fails where the system pinches it. If you’re using bungees and hooks (common for barrier setups), the attachment style becomes part of your construction decision, not an afterthought. This product is a clean example of that “net + retention method” reality: durable nylon golf barrier net with hooks and bungee cords

Braided netting

Braided is what you buy when you’re tired of replacing things.

Braids usually resist abrasion better than simple twist, and they tend to keep structural integrity when they’re rubbing against frames, poles, and hardware. Facilities love braided for a reason: less fray, less sudden failure, fewer “why did it break right there” moments. If you’re building something with constant tensioning, roll-away frames, or repeated setup/tear-down, braided construction typically pays back.

But here’s my unpopular opinion: some braided nets are “thick” in the wrong way. They sell bulk, not performance. If the build is heavy but the finish and edge reinforcement are mediocre, you still lose—just later, and more expensively. When you’re evaluating braided candidates, look at the full system: frame contact points, edge finishing, tension method.

Woven netting

Woven behaves differently. It’s less “net” and more “fabric that acts like net.”

That’s good when you want predictable deflection and energy absorption instead of rebound. Impact screens are the obvious case. If you’re building a simulator environment, you generally want a controlled, repeatable response—less ricochet, more absorption—plus a face that behaves consistently under repeated strikes. That’s why woven-type constructions belong in the simulator enclosure conversation, not in the same bucket as a backyard barrier net. Here’s the category reference I use for that mental split: professional golf simulator enclosure impact screen setup

Now ask yourself: are you trying to catch energy, or return it?

Because that question decides whether woven is a smart choice or an expensive mistake.

Netting construction types: what fails in the real world

Buyers love “material.” Nylon, PE, polyester. Fine. But I care more about failure mode than fiber name.

Here are the common ones:

- Edge loading: corners tear because tension concentrates where the net is forced to behave like a rope.

- Abrasion: the same contact points grind down—frame rub, hardware rub, ground rub.

- Cyclic fatigue: impact hits the same zone thousands of times and the net slowly loses stiffness, then suddenly gives up.

- Geometry drift: the mesh opens and rebound changes long before you see visible damage.

And yes, sourcing region changes how fast those show up. Resin grade, coating discipline, UV package choices, and QA culture are not evenly distributed. That’s not moral judgment. That’s procurement math.

“Best netting construction for industrial applications” depends on what you’re really doing

People say “industrial applications” like it’s cranes and factories. In practice, a sports facility with daily use is industrial. A training academy is industrial. A commercial simulator bay is industrial. The net sees more impacts than many warehouse barriers ever will.

If the install has moving frames, repeated tensioning, and constant abrasion, I start by looking at systems designed for that kind of life—then I specify construction to match. This is exactly why I like referencing mobile, adjustable units when talking about durability: adjustable multi-sport net with rolling base and casters

And if portability is the defining stressor—assembly friction, transport abrasion, repeated pack/unpack—the failure pattern changes again. Portable pickleball systems are a perfect example of “non-impact stress” driving wear: portable pickleball net with steel frame and support feet

Finally, high-impact containment (golf cages) is its own beast. Impacts concentrate. The strike zone is real. If you’ve never seen a cage net fail exactly where everyone hits… you haven’t owned one long enough. For that category: large golf practice cage net for outdoor swing training

Comparison table

| Construction | What it’s good at | What I see fail first | Best-fit uses | Buyer trap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knotless netting | Even load distribution, cleaner rebound, fewer hard stress points | Mesh “bagging” if joins/yarn are weak | Golf cages, repeated-impact zones | Assuming knotless = premium without checking deformation risk |

| Twisted netting | Low cost, quick production | Twist relaxation + abrasion at attachments | Light-duty barriers, temporary setups | Over-tensioning and expecting geometry to hold |

| Braided netting | Better abrasion resistance, stable under cyclic strain | UV/finish weakness shows up at edges and contact points | Facilities, high-friction installs | Paying for thickness instead of construction quality and finishing |

| Woven netting | Predictable deflection, energy absorption | Edge fray and seam wear if finishing is weak | Simulator screens, controlled impact absorption | Using woven where rebound is desired |

FAQs

How is knotless netting made?

Knotless netting is made by forming mesh intersections without traditional knots, using a continuous looped or joined structure so load spreads more evenly and stress points are reduced. In practice, durability depends on the joining consistency, yarn quality, and edge finishing—because that’s where deformation and tearing begin.

Knotless vs knotted netting: what’s the actual difference?

Knotless netting uses non-knotted joins to reduce hard stress points and improve uniform load distribution, while knotted netting forms intersections with knots that can create abrasion points and variable rebound but can hold geometry well when built correctly. The right choice depends on impact frequency, abrasion exposure, and whether rebound consistency matters.

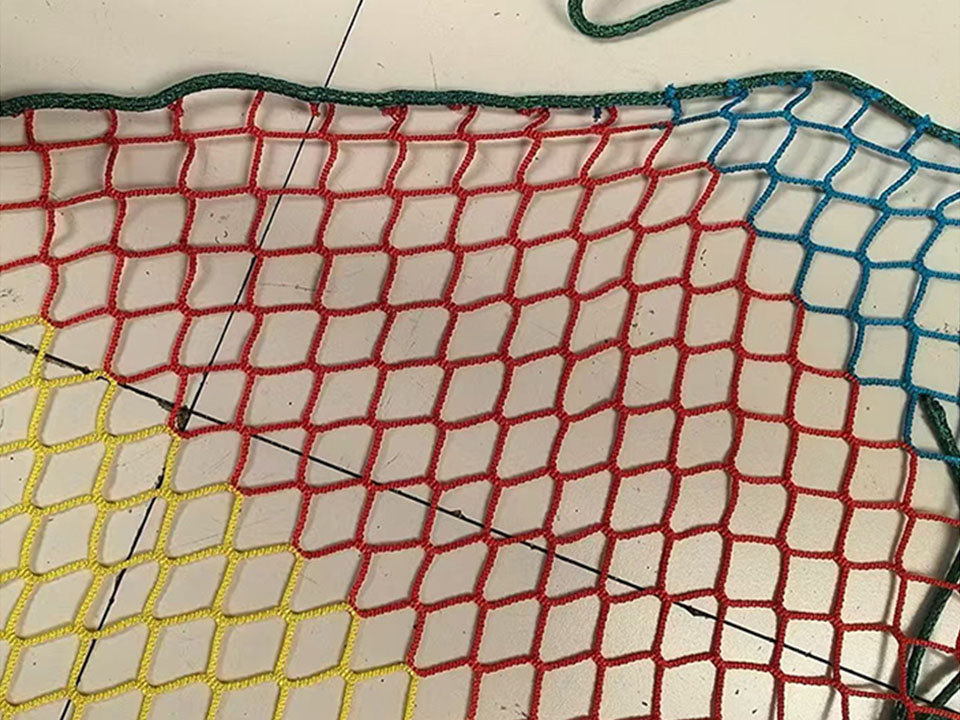

What are the main netting construction types?

The main netting construction types are knotless, twisted, braided, and woven, defined by how strands are built and joined, which determines load distribution, abrasion resistance, and how the mesh behaves under repeated impacts. If you match construction to the dominant failure driver, you get fewer surprises and a longer service life.

What’s the best netting construction for industrial applications?

The best netting construction for industrial applications is the one that matches your dominant stress pattern—abrasion, cyclic impact fatigue, edge loading, or controlled deflection—rather than a one-size “best” label. For high-abrasion setups braided often wins, for repeated impact zones knotless is usually safer, and for impact absorption woven is the better tool.

CTA

If you want to stop buying nets twice, stop shopping by material name and start shopping by construction and use case. Browse the full catalog, shortlist by application, then demand the construction that matches your failure risks: FSportsNet products and the main hub for categories and specs: FSportsNet.